The history of Cappadocia has to begin with the geological background. A very long time ago a series of eruptions from the cones of Mt. Erciyes and Mt. Hasan covered the area in a thick layer of volcanic ash which solidified to form the soft tufa that characterizes the surface strata. These volcanic mountains dominate the landscape today. Erciyes offers reasonable skiing in the winter.

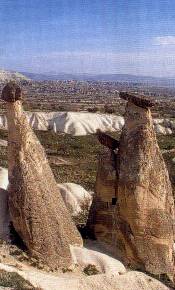

The processes of erosion started the work of carving out valleys and gorges and continue to this day. The signature of the region, the 'fairy chimney' is formed when a cap of resilient stone protects the column of softer material beneath it while the surrounding tufa is removed. The area is now a warren of caves, underground cities, rock churches and chambers and it's almost certain that there are more such sites waiting to be rediscovered.

Cappadocia makes its first entrance into history courtesy of Heroditus, writing in the 5th Century BC but it is with the advent of Christianity that it becomes of interest to the average contemporary tourist. Christianity came early to the region with St. Paul passing through on his way to Ancyra (Ankara) and 3 Saints originating here in the 4th Century.